Friends who are an important part of Timmins’ golden history will gather to share memories and mining stories this weekend.

The Pamour Mine Reunion takes place Saturday, Nov. 20, at Albert’s Hotel in Timmins, beginning at 7 p.m.

The Pamour operated from 1936 to 1999 under the ownership of different companies on a piece of land in Whitney Township once described as a “moose pasture.”

The mine closed in 1999 after Royal Oak, the company that owned it at the time, went bankrupt.

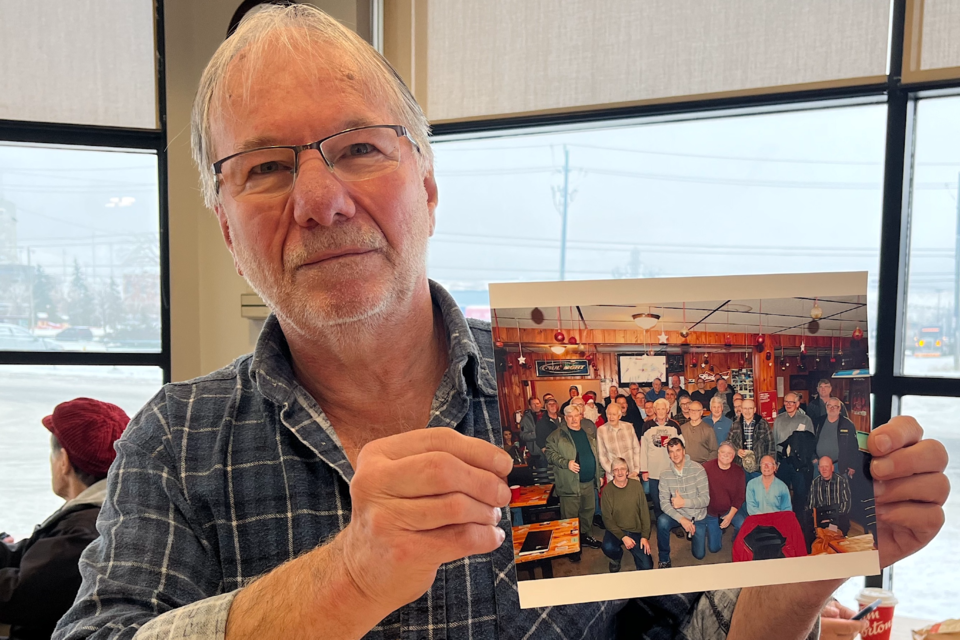

Former Pamour employees have been getting together since the mine closed. J.P. Rozon started the reunions and has kept them going for the past two decades. Former employees of the McIntyre, Pamour, Hallnor, Aunor and Knighthawk mines can attend, as all the mines were owned by the same company. Those wishing to stop by are asked to call Rozon in advance at 705-267-5370.

“I was in the recreation club (for the Pamour),” he said. “I did my first reunion when the mine closed. I partnered up with Pick of the Crop and made up over 240 food baskets and handed them out at the first reunion.

“When the mine closed, because the company went bankrupt, nobody got severance pay, nobody got pensions. Nobody got nothing. And some people were living payday to payday and they were struggling.

“When you were in the rec club, $2 would come off your pay and the company would match that. I was the finance guy for the rec club. I’m the one who had that money in the bank and access to that account. I said, the mine doesn’t exist anymore. What do I do with the money? I did over 240 food baskets with ham and turkey — you could hardly lift them. I spent the money on the people. So, I organized a reunion and handed it all out.

“After that, I thought we might as well keep the reunion going.”

The property that eventually became the Pamour was thought to be good for mining from the beginning of the Porcupine Camp. The June 1, 1936, edition of The Porcupine Advance covered its opening.

“The story of how the mine came to be developed was told at the banquet in the evening,” the story reads. “R.M. Macaulay, field engineer a couple of years ago for Quebec Gold, first saw the possibilities of establishing a real mine where Pamour is today. He knew it would take a lot of money. In Oliver Hall, he found staunch support for his belief. Mr. Hall through (an interest of) Noranda money in the venture and was at New York to meet J.Y. Murdock when he landed there following a trip to Europe. He convinced the Noranda president, who took it to his board of directors. They decided to put up the money.

“The period of hard work that followed brought many a moment when it looked as if production would not be possible until long after the specified time. But on Saturday night it was announced that the job had been completed a couple of weeks ahead of schedule and for $90,000 less than the original estimate.

“William Meen, ‘representative of the old guard,’ formerly of the LaPalme company, from whom Pamour took over part of its property, said he’s always had the idea there ‘was something underneath this moose pasture.’”

Rozon worked a total of 42 years in mining. He spent 15 years at the McIntyre Mine, 10 at the Pamour, then worked at Kidd Creek following the Pamour’s closure.

“I was the maintenance guy,” he said. “I repaired a little bit of everything. I worked on surface and underground. I worked on pretty much any piece of equipment you can imagine.

McIntyre was underground maintenance and mill maintenance and at the Pamour, I worked underground and in the mill both.”

He recalled what it was like working at the old McIntyre Mine and the Pamour.

“When I started underground at the McIntyre, every level, if you wanted to use a telephone (it) was a crank telephone,” Rozon said. “There was a chart on the wall. It had three long and two short (cranks) for this guy. Three shorts and four longs for that guy. That’s for every level of the mine, which at that time was the deepest gold mine in the world.”

Battery power became vital for moving ore from the underground.

“When I was underground at the McIntyre and the Pamour, I was in charge of the locomotives,” he explained. “I had something like 60 pieces of equipment that I maintained. These locomotives were battery-operated. A lot of people think today that the cars made with batteries are something new. I was working on that in the ‘70s, and they were made in the ‘60s.

“The batteries were as big as this table. You would charge them up and fill your cars with up with ore and dump it in the ore pass. Every level had cars and locomotives. If your battery died, you switched batteries and kept working. People think the batteries are new, but it's old.”

Such innovations were part of the Pamour’s history. The mine was considered the “most modern mining plant in Canada” when it first opened, according to the headline in The Advance.

“It is no novelty in the Porcupine now to have a new mine come into production, but Saturday’s official opening of the Pamour Mine was something like the opening of the Dome just over 24 years ago,” the story read. “The intensive exploration of the vast area to the east of producing part of the Porcupine is now going on as a result of Pamour’s success to date.

“A year ago, a lot of the buildings were going up at Pamour. Astute mining men were shaking their heads since attempts to develop the same ground almost from the beginning of the Porcupine have failed. On Saturday, prominent mining and financial men of Canada saw the most modern mining plant in Canada using 500 tons of ore every 24 hours. They saw a mill such as engineers must dream about. They saw a surface plant built for permanency capable, with few alterations of taking care of more than twice the present tonnage.”

The best part of the mine’s history for the workers who regularly attend Pamour Reunions is the friendships.

“What was great about working there was the rec club. That rec club meant everything to a lot of people who worked there,” Rozon said. “There were about 10 members of the rec club who were hourly employees and a couple who were mine staff employees. We’d get together once a month and schedule events.

“We had skating events, where we would rent the arena. We would rent the pool at the Sportsplex. We would have Christmas parties for the kids. Summer parties in the Hollinger Park. We’d have dances for the adults. We’d have darts and crib nights. Everybody took an event to take care of. All the meetings we did were on company time.

“The club was hourly and staff mixed. So, everyone who attended were hourly and staff. Everybody got to know each other and form friendships. That’s why it is nice to keep it going.

“We had the reunion 21 years in a row. Then two years because of COVID, we didn’t have it. But now, we’re out of COVID jail, so let’s have a reunion.”

To prepare for the reunion, he canvasses local businesses for draw prizes. He also works the phone to contact former employees.

“People in their 70s and 80s don’t do emails,” Rozon said, with a laugh. “There are a lot of good memories. There’s mining talk. There’s talk about the rec club. We share old memories. There are a lot of long-term friendship created because of the club.

“A lot of the people have moved out of town. I call them. Sometimes they can’t make it. But the odd time one guy will come from Sarnia or something and it’s nice to see them.”

His goal is to keep the reunion going in the future.

“After 42 years in the mines, you make a lot of friendships,” Rozon said. “You don’t miss the work, but you miss the people.

“I’m trying to keep it going as long as we can.”