Like so many small towns, Espanola, Ont., holds tight to some unique claims to fame. Dubbed “The Home of Ringette,” it’s the place where Mirl “Red” McCarthy organized the inaugural game of the experimental sport, now played by thousands of skaters across the country. Espanola (population 5,185) was also the longtime summer home of actress Lois Maxwell, best-known for portraying Miss Moneypenny in 14 consecutive James Bond movies, from Dr. No in 1962 to A View to Kill in 1985.

Today, Espanola is still what it has been for decades: a relaxed, picturesque pulp-and-paper town 45 minutes west of Sudbury, and the main service hub for nearby Manitoulin Island. Many locals earn their paycheques from the mill while savouring the spoils of rural Ontario life, from breathtaking scenery to tight-knit neighbourhoods.

In all fairness, Espanola is probably most famous for being a place people drive by. Nestled a few kilometres south of the Trans-Canada, it’s just far enough away from the highway that cars whizzing by never actually see it.

Most out-of-towners didn’t see this, either: a February press release from the local Ontario Provincial Police detachment, announcing the fruits of a search warrant executed at a duplex on Arthur Court. Officers on scene seized more than $26,000 worth of fentanyl, cocaine and crystal meth, the news release said, and arrested three people—including two men who live in neighbouring apartment buildings on Lawrence Avenue East in Scarborough, a 4½-hour drive from tiny Espanola.

Although the press release did not mention this fact, one of those handcuffed suspects—Devontae Davis-Biggs, 28—is well-known to police in his home city. Once accused of being connected to the notorious Orton Park street gang, he was arrested nearly a decade ago as part of Project Quell, a high-profile investigation aimed at taking down two rival Toronto gangs that were waging a violent east-end turf war at the time. All told, Davis-Biggs was charged with 11 offences in connection with Project Quell, including drug trafficking and participation in a criminal organization.

Here’s what else that OPP press release didn’t say: the winter raid in Espanola was hardly an isolated incident. According to court records obtained by Village Media, Davis-Biggs was arrested two other times during the previous six months for allegedly dealing hard drugs in northern Ontario: first in July 2021 in the Township of Northeastern Manitoulin (population 2,600), and then again in September on Wikwemikong First Nation, 100 kms from Espanola. Both times, Davis-Biggs was charged with possession of fentanyl for the purpose of trafficking, among other offences.

As the opioid crisis continues to kill Canadians at a seemingly unstoppable pace, police across Ontario are grappling with more and more cases just like this: drug traffickers from the Greater Toronto Area—some with known ties to established street gangs—branching out into rural, northern and First Nations communities, where low supply and high demand equals huge profits. In many instances, gang members are literally driving into town and taking over locals’ houses.

It’s as much a business story as a crime story. And business is booming.

“The OPP has seen a proliferation of street gangs from our larger urban areas into our more rural towns and cities,” says Bill Dickson, a spokesman for the Ontario Provincial Police. “Organized crime groups, including street gangs, are opportunistic. They operate where they will receive the most profit, as their criminal activities are always motivated by profit.”

Like so many consumer goods, legal or not, drugs like fentanyl grow more valuable the further they get from the big city. For entrepreneurial street gangs willing to embark on some road trips, there is plenty of money to be made.

“If you look at the GTA as one of the epicentres [of drug distribution], by the time you get to Thunder Bay or North Bay that ounce of product, whatever it might be, is going for three or four times what it’s sold for in Toronto,” says Steve Watts, a Toronto police superintendent who works in the Organized Crime Enforcement Unit.

Toronto-based gangs are increasingly chasing that enormous profit potential, Watts says, emboldened by the belief (however wrong) that they can fly under the radar of local law enforcement. “They’re not known to the local police,” he says. “They’re not known to the local community. At least initially, they can operate with impunity.”

They bring their 'big city' stature with them.

Antonio Nicaso agrees. A lecturer at Queen’s University and a leading expert on organized crime, he has seen countless examples of profit-driven street gangs expanding far outside their traditional stomping grounds.

“There is a market because there is a demand in smaller communities,” Nicaso says. “In smaller communities, there is also less police presence, less intelligence, so they try to keep a low profile. That’s the trend and you can see that practically everywhere.”

Indeed. Throw a dart at a map of Ontario, and chances are you will hit a community that’s already been infiltrated by Toronto-area gang members—and a corresponding police operation aimed at taking them down.

Project Kraken, an eight-month investigation involving multiple forces in 2019, led to dozens of arrests, hundreds of charges, and the seizure of 23 firearms, all linked to Scarborough’s Chester Le gang. Police alleged that the group was a “coordinated criminal organization” trafficking massive amounts of fentanyl and cocaine into multiple cities, including Peterborough and Sudbury.

A year later, authorities in Thunder Bay initiated Project Trapper, a three-month drug-trafficking probe that led to 32 arrests and 119 charges. Police said 15 of the accused were from the Greater Toronto Area and had “suspected or confirmed links to street gangs.”

In October 2020, Toronto police revealed one of the largest takedowns yet: Project Sunder, a drugs-and-guns bust that exposed the enormous province-wide tentacles of the Eglinton West Crips. Although the case began as a local Toronto investigation, it grew to involve 15 other jurisdictions, including Gravenhurst, Napanee and Sault Ste. Marie.

At a press conference announcing Project Sunder (114 arrests and nearly 800 charges), a senior OPP officer did not mince words about the increasingly dangerous reach of GTA street gangs into other regions of the province. “These criminal networks are opportunistic,” Chief Superintendent Paul Mackay told reporters. “They prey on our most vulnerable.”

Need more proof? Look no further than Simcoe County, and a recent investigation dubbed Project Garfield.

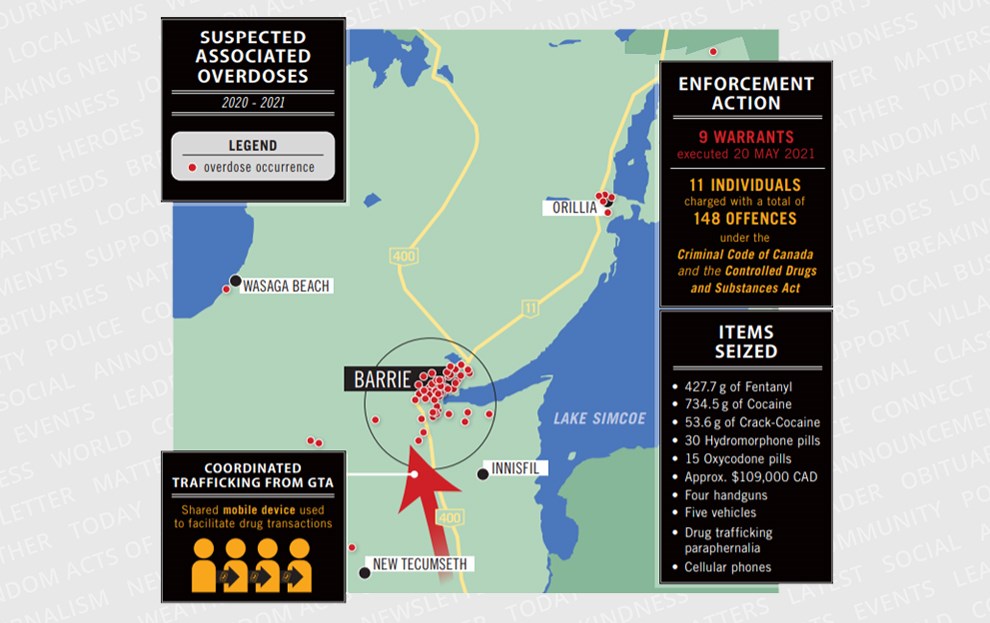

Teaming up with police forces in Barrie and Toronto, a Central Region OPP unit spent months conducting surveillance on a group of Toronto-area gang members who viewed Simcoe as nothing more than an untapped business opportunity, human lives be damned. Working in shifts with a shared cell phone, the group would drive up one or two at a time, peddling fentanyl, cocaine and crack to customers from Coldwater to Nottawasaga to Huronia West.

“These accused persons did not live here,” said OPP Det.-Sgt. Greg Beamer, speaking last September to a virtual meeting of the Orillia Police Services Board. “They literally came to our communities to exploit the vulnerable people in the community and take advantage of the drug trafficking networks that were here.”

The investigation was so intricate that police were actually able to link the gang to dozens of specific fatal and non-fatal overdoses across the county. In total, officers seized 428 grams of fentanyl, 787 grams of cocaine, $109,000 in cash, four handguns and five vehicles—including two Audis and a BMW.

A few months after Beamer’s police board presentation, OPP officers in Simcoe arrested yet another reputed gangster from the GTA: 23-year-old Jerome Pantlitz-Solomon. An accused member of the Mississauga Crips, he was picked up three years earlier for allegedly dealing cocaine in Wasaga Beach. Following a nine-month investigation that targeted fentanyl traffickers in Collingwood and Stayner, he was pulled over in January and arrested again—this time with a .45 caliber handgun in his car, along with more cocaine. (The charges against him have yet to be tested in court.)

“Street gangs, or other urban-based organized crime groups, continue to develop province-wide criminal networks and are increasing in sophistication,” says Dickson, the OPP spokesman. “Their migration, size and scope have provincial impacts which requires the OPP and other partners to work in collaboration. Project Garfield was an example of this collaboration. The OPP has worked with many municipal police services on similar investigations, where GTA-based street gangs operate drug trafficking networks in more rural communities, including northern Ontario.”

Hugh Stevenson knows exactly what Dickson is talking about. Chief of the Sault Ste. Marie Police Service since 2018, Stevenson has seen that troubling trend firsthand, with devastating consequences.

“Northern Ontario towns are a significant market for GTA drug dealers,” the chief says. “We have seen an increased amount of drugs-slash-poison being brought into our community. They bring their poison up here, they cut it further and they put it on the street.”

Algoma District, which includes the Sault, has one of the highest overdose death rates in the province. According to the latest available statistics, there were 46.5 overdose fatalities per 100,000 people in 2020, more than triple the rate from the previous year. At least some of those deaths were the result of toxic drugs being driven to Sault Ste. Marie by southern Ontario traffickers.

“We will continue, as a police service, to investigate thoroughly every allegation of drug dealers, proactively and reactively, coming into this community,” Stevenson says. “We will surveil you. We will bring you before the courts.”

That is much easier said than done, of course. Although the Ford government recently announced a $75.1-million investment to target gangs and gun violence—including the creation of a “mobile prosecution unit” that will operate in “priority regions across the province”—there will never be enough resources to target every ounce of fentanyl floating around.

And as police forces have learned in recent years, Toronto-based traffickers who branch out to smaller communities have their ways of keeping potential informants quiet. Violence, intimidation—and loaded handguns—are all part of the trade.

Det-Sgt. Dan Irwin, a member of the Thunder Bay Police intelligence department, has seen the process far too often: A newly arrived drug dealer reaches out to a local resident with a kind gesture. Maybe it’s an offer of food, or designer clothes. Usually it’s fentanyl or crystal meth. Once that favour is granted, it must be reciprocated.

“They say: ‘I’ll give you some drugs if I can stay here for a night,’ ” Irwin says.

But then one night turns into two nights, then a week, and in time the house is being used solely for drug deals. “It turns into a trap house,” Irwin says. “They want them out of the house, but they can’t get them out. They’re scared for their safety.”

Irwin says his police force investigates these types of trap houses on a "weekly basis."

Many Indigenous communities in Ontario are struggling with the same scourge of unwanted visitors.

Brad Duce is a detective-inspector with the Nishnawbe Aski Police Service, the largest First Nations police force in Canada, responsible for 35 northern communities spread out over two-thirds of Ontario. He says some of the regions he serves have fallen victim to predatory drug dealers who “bring their ‘big city’ stature with them," not to mention their weapons.

“We have definitely seen an exponential increase in the influx of individuals from the larger urban cities, specifically the GTA, trafficking illicit narcotics to the First Nation communities,” wrote Duce, in an email interview with Village Media. “They use their gang ties and influence to prey on individuals suffering from alcohol and drug abuse to help them facilitate their ‘foothold’ within the community. They establish themselves as the main source of the drug supply as the community members continue to fall victim to their addictions.”

Tragically, Duce says, some residents fork over every last dollar to these out-of-town drug pushers instead of buying food and clothing for their children. “With the influx of individuals associated with gangs,” he says, “they also employ violence to establish themselves to control and expand their drug trade.”

The people of M'Chigeeng First Nation, on Manitoulin Island, understand exactly what Duce is talking about. Earlier this month, a man in their community was shot and killed, and five other men were later arrested and charged with first-degree murder. Neither the victim nor his accused killers were band members. All six are from Greater Toronto, including Newmarket, Markham and Brampton.

In the wake of the shooting, M'Chigeeng Chief Linda Debassige made an impassioned plea on Facebook.

“We know that there are members of our community who know of this illegal activity,” she wrote. “We understand that these violent individuals are preying on your vulnerabilities to use you to get what they want. They are using you to continue to hurt members of our community—our families and our friends. We want to remind you that there is a way out of these situations.”

“I ask you to think about our loved ones, our families, our children of our community, our elders, our friends, our infants that are yet to be born,” Debassige continued. “I ask you to think about our ancestors who have gone before us. Is this what we want of our community? Do we want the next shooting to be one of them? No, we don’t. We can stop this but only if we do it together.”

M'Chigeeng endured a similar shooting just six weeks earlier. Police are still searching for the alleged gunman, 30-year-old Prince Almando Graham of Toronto, who is wanted for attempted murder. Also known as 'P,' he is considered armed and dangerous.

As for Devontae Davis-Biggs, his rap sheet continues to grow.

Despite his many run-ins with the law, court records show he was not ultimately convicted in the Project Quell raids that targeted the Orton Park gang a decade ago. For reasons that aren’t exactly clear, all charges against him were quietly withdrawn long after the case triggered so many sensational headlines.

Now facing a long list of fresh drug-related charges, Davis-Biggs has hired a Toronto lawyer, Brian Kolman, to defend him. Kolman tells Village Media that his client intends to plead not guilty to all offences and is “presumed to be innocent” unless proven otherwise at trial.

On April 27, after two months in custody following his February arrest in Espanola, Davis-Biggs was granted bail with strict conditions. He must live at his Scarborough apartment, abide by a curfew (home by 11:00 p.m.), and avoid all contact with any of his co-accused. He is also prohibited from possessing any weapons or "unlawful drugs or substances," according to the release order signed by Justice of the Peace Holly Charyna.

The only time he is permitted to step foot in Espanola or Manitoulin Island is for court dates. His next appearance is scheduled in Gore Bay for May 18.

Davis-Biggs should have no trouble finding the courthouse. If anyone knows his way around the area, it's him.

Stephen Petrick is a freelance journalist based in eastern Ontario. His work has earned five awards from the Ontario Community Newspapers Association.