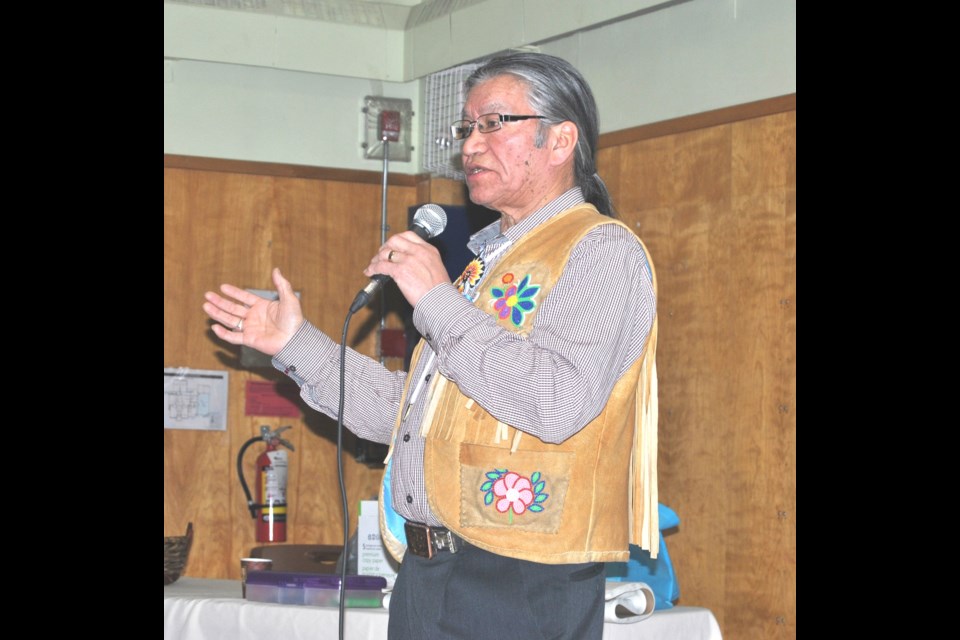

Edmund Metatawabin, author of Up Ghost River and former chief of Fort Albany First Nation, spoke this week to about 100 students and teachers at the Timmins Native Friendship Centre about his experience of abuse at the notorious St. Anne’s Residential School in Fort Albany.

Prior to addressing the child abuse issues at residential schools, Metatawabin gave background about the spirituality, knowledge and accumulated culture of his people, the Omushkego or Cree, describing the concepts of family, caring for the sacred family, and the origins of the mother-centred social systems.

The First Nations had an evolved social and spiritual system, but the unwillingness of government and religious leaders to accept this lead to the use of the education system as means of stripping away the cultural identity of First Nation youths, and ultimately their culture, by forcibly removing a child from his family, isolating them at a residential school, forbidding them from speaking their language or following their beliefs.

At age seven, Metatawabin was forced to attend St. Anne’s Residential School.

“My parents had no choice. If they didn’t follow the church’s instruction, the priest would go to the Hudson Bay Post and arrange it so you couldn’t buy things to live on; they wouldn’t accept the furs your father had trapped and you couldn’t fend for your family,” recalled Metatawabin.

On his first day, Metatawabin was punished for running into a washroom and through a window to watch his father leaving.

“As I watched my father leaving, a nun yelled at me to leave that room at once,” he said.

I got slapped; I got hit and hit the wall on the other side of the room.”

“That was my baptism,” Metatawabin said. “Now you are going feel the changes, you are going to feel pain, you are going to lose your hair, you are going to get slapped,” he added.

Metatawabin demonstrated with his hands how the nuns and brothers hit the students from one side of the head, then the other side of the head, and then with both hands on both sides of the head simultaneously.

“At times, I was punished by being forced to kneel with legs crossed for up to 30 minutes on the hard floor,” said Metatawabin getting down on his knees to demonstrate to the class. “Do you know what that can do to your knees?

“My knees have not been right since,” he added. “A friend was forced to kneel for 60 minutes — try it sometime and see how it feels.”

Perhaps the cruellest punishment endured was being placed twice in a crudely constructed electric chair.

“We had to hold on to the handles and couldn’t let go as the electrical charges went through our bodies and our tiny legs kicked away in the air,” he said.

Another form of cruelty was being forced to eat a bowl of porridge that he had vomited in few days earlier while sick.

Metatawabin also recalled what he called the dangerous night times when the monsters came out, recounting specific instances of abuse against students. The descriptions were sometimes graphic.

“That was the life we lived as children until we were able to leave after eight years,” Metatawabin stated.

“You cannot be surprised that the father takes up the bottle and tries to forget what has happened to his little boy,” explained Metatawabin

Telling someone about the abuse he experienced was the best way for him to cope and rid himself of his demons Metatawabin told the students.

Students and teachers from Timmins High and Vocational School, Ecole Secondaire Cochrane High, Kirkland Lake District Composite School, Roland Michener Secondary School and Kiskinohamatowin (Alternative Learning Program) not only listened to Metatawabin’s speech but also participated in several exercises that drove home the impact the abuses at St. Anne’s Residential had on the psychological wellbeing of the students.

Last year, the Ministry of Education instructed school boards to teach the impact the residential schools has on First Nations as part of the Truth and Reconciliation process.

“DSBONE hired Lisa Innes to be Indigenous Systems Lead and a group of history and indigenous education teachers calling themselves, 'Facing History,' have met three times to talk about identity, reconciliation, colonization ,” said Michelle Leigh Superintendent of Schools for DSBONE. “The last time they met was Monday and Edmund joined us an elder and a residential school survivor.”

From 1992 to 1997 OPP interviewed 700 witnesses about the abuses at residential schools. Six convictions resulted, but according to Metatawabin no religious leader was ever charged with any crimes.

Metatawabin and another person are still seeking compensation for the abuse they suffered. In December, 2016 the two made application to Ontario Superior Court for compensation and for an inquiry on why the OPP evidence was not submitted to the Truth and Reconciliation process thereby denying victims of compensation. Victims had to sue to have records released in 2014.

A decision is expected to be made by Justice Paul Perell in March.