OTTAWA — The leaders of three First Nations police services in Ontario are sounding the alarm over lapsed funding agreements with the federal government.

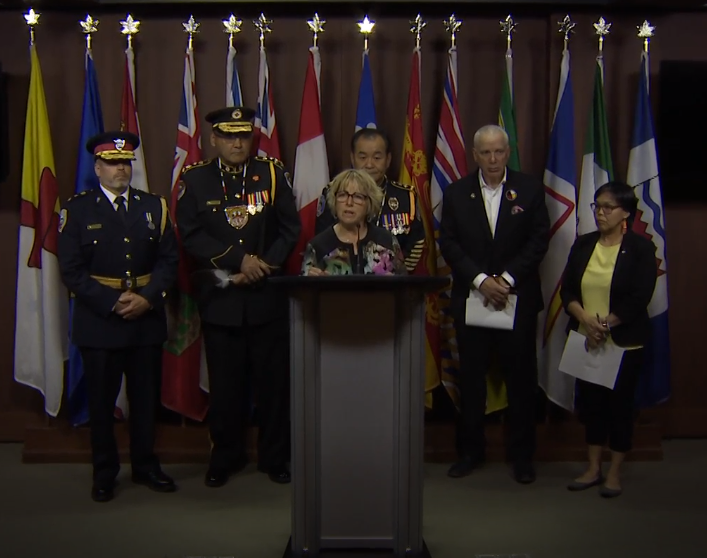

Before a federal court hearing on a motion for emergency relief brought forward by the Indigenous Police Chiefs of Ontario, policing leaders held a press conference Monday to announce their intent to hold the federal government accountable.

As of March 31, renewed funding agreements with Public Safety Canada have not been in effect, which affects 45 Indigenous communities that are home to about 30,000 people.

"This is a dark time for our communities. Our funding is running out quickly," said Anishinabek Police Service Chief Jeff Skye.

Skye said he is proud to serve his community, but without a funding agreement in place he “cannot guarantee [his] communities’ safety.”

“I have no say in the matter. I have no obligation once that ends our police service. Our women, our children; our officers that swore the oath to protect them will no longer exist. That’s on Canada, not on the Indigenous people,” said Skye.

Just over half of the funding — 52 per cent — comes from the federal government through Public Safety Canada, while the remaining 48 per cent is funded through the Ontario government.

Treaty Three Police Service Chief Kai Liu announced that “the Treaty Three Police, as of June 5, wrote our last paychecks to our members on the funding residual that have been leftover from the previous five-year funding agreement.”

Liu said the chronic underfunding of the Treaty Three Police Service has left many First Nations communities understaffed, leading to lengthy emergency response times.

“Many communities don’t have 911, let alone get a response. However, if someone did get a hold of the police, it would take us, at times, one to three hours to respond because they just do not have enough officers to travel the 55,000 square miles that we police,” Liu said.

Anishinabek Nation, Grand Council Treaty Three, and the United Chiefs and Councils of Mnidoo Mnising have declared states of emergency as a result of the situation.

“Put it in the shortest and simplest of terms, [Canada] operates in the most extraordinarily racist way,” said Julian Falconer, a lawyer representing the Indigenous Police Chiefs of Ontario.

Falconer said Indigenous police services are not only chronically unfunded, but they are unable to have basic police specialty departments such as domestic violence units, homicide units, and emergency response, and owning or financing property such as a police station.

“They are prohibited from having that,” Falconer said.

Police leaders have opposed and criticized Public Safety Canada’s “take it or leave it” approach, and the Indigenous Police Chiefs of Ontario have said they will not sign any agreement that is deemed discriminatory.

“There is no operational plan, none, to ensure the safety of over 30,000 people. They are literally waiting the situation out in silence,” Falconer said. “Canada says sign anyway. It’s appalling.”

Dougall Media has contacted spokespeople for Indigenous Services Minister Patty Hajdu but has yet to receive a response.